Geoff Egan, a former President of SPMA and serving Vice-President, died in 2010. To honour his work we hold the Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture each year. Geoff’s influence on medieval and post-medieval artefact studies has been, and will continue to be, very considerable and far-reaching. To read some of the kind tributes of Geoff’s many friends and colleagues see Post-Medieval Archaeology volume 45/2 (2011).

The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2025

We are delighted to announce that the 2025 Geoff Egan Memorial Lecturer is Dr Beatriz Marín-Aguilera. Book your free ticket!

The lecture and drinks reception will be taking place during the Theoretical Archaeology Group Conference (TAG) in York, UK. We look forward to welcoming you at the York Medical Society on 16 December. The lecture starts at 18:00 and is followed by a drinks reception. As always, the lecture will be free to attend: attendees need not be delegates of TAG. Find out more about the venue in our News Story.

Dr Marin-Aguilera is Lecturer and Derby Fellow in Historical Legacies of Empire at the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology at the University of Liverpool. Previously a Renfrew Fellow at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at the University of Cambridge, her research centres Indigenous agency and decolonial approaches in the ancient Mediterranean and the colonial Americas thorough the materiality of everyday life.

Her current project, ‘Anticolonial Caribbean Futures’, runs in collaboration with the Kalinagos in Dominica, the Taínos in Jamaica, the University of the West indies, Afro-Indigenous descendants in the UK, the SDCELAR-British Museum, and National Museums Liverpool.

Dr Beatriz Marin-Aguilera: An Archaeology of Radical Tenderness

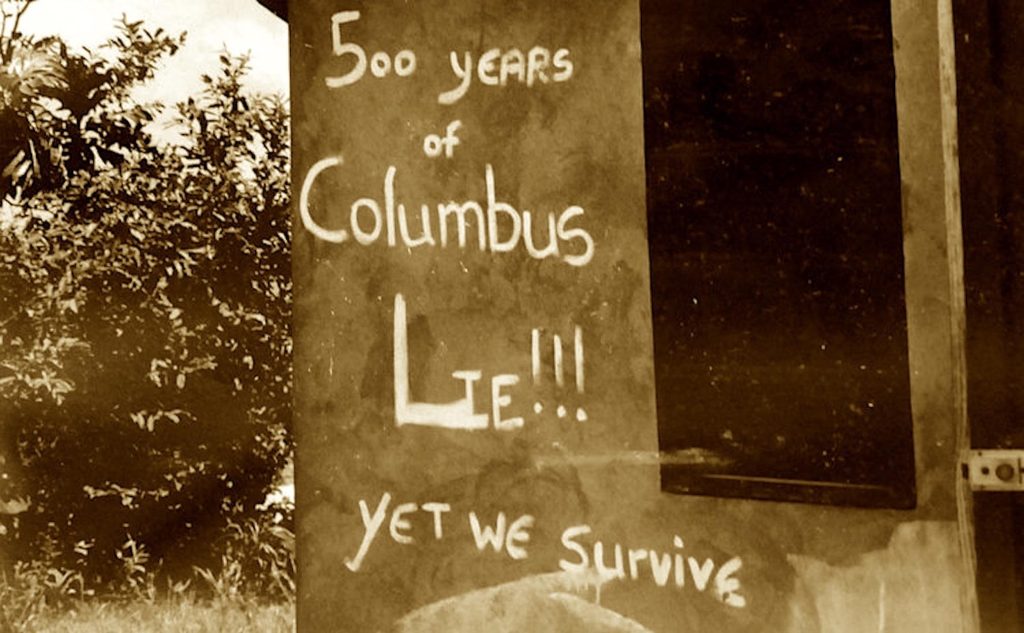

Archaeology as a discipline is at an ethical crossroad. Claims to be neutral and to depoliticise our practice – or to defend the status of archaeology as an ‘objective science’ – have alarmingly (re)gained traction. This turn away from humans (past and present), their suffering, and the ethics of care is the product of unaddressed postcolonial demands that hide our privileged position as (white) archaeologists.

Drawing on a long tradition of the social in Latin American arts and scholarship, I propose an ‘archaeology of radical tenderness’ that combines protest and profound critical thought with deep care, affection, and vulnerability, especially in the face of systemic harm and oppressive political structures. Using the archaeological record and the living experience, the archaeology of radical tenderness challenges inherited power structures and colonial histories offering new alternatives for our discipline as a site of openness, resistance, and relatedness. The archaeology of radical tenderness advocates for an embodied-situated practice and a critical and loving approach to social justice, emphasising collective care, the transformation of communities through shared vulnerability, and the healing needed to birth new (more equal) futures.

The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2024

The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture and drinks reception took place during the Theoretical Archaeology Group conference (TAG) on 15 December at Bournemouth University.

Professor Laura McAtackney: The potentials and limits of conducting archaeologies of the Northern Ireland Troubles and peace process: reflections over 20 years.

The question that has haunted me through my research career has been what are the potentials and limits of material culture in revealing unresolved aspects of difficult recent pasts, most specifically in the conflict and peace in the North of Ireland? It is a question I have been trying to answer for over twenty years and one that has involved engaging with various material forms that have constantly been in motion and in flux. My first inclination was to turn to an ‘icon’ of the conflict, Long Kesh / Maze prison, as a monumental and materially rich site that was largely off-limits to researchers. The politics of its inaccessible dereliction meant I had to consider it in an expansive way as a place with ‘distributed self’ (2014) that materially and psychically reached far beyond its confines and deep into communities. It was in those communities that I eventually started traversing streets and noting their ever changing configurations of murals, graffiti, and grassroots memorials creating memoryscapes alongside enduringly materialized segregation, so-called ‘peace walls’. More recently, I have thought on how my understandings of the conflict has been shaped not only by presences but also absences; a place with a desire for peace but also fear of forgetting injustices. Ultimately, my faith and despair in material answers to loaded questions has evolved in ways that I could never have foreseen at the start and so this lecture will consider what under-explored pasts have been revealed and what are the limits of the material in knowing the contemporary.

Laura McAtackney is Professor in the Radical Humanities Laboratory and Archaeology at University College Cork, Ireland, and Professor of Heritage Studies at the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, Aarhus University, Denmark. She is also Docent in Contemporary Historical Archaeology at the University of Oulu, Finland. Amongst many interests her research focuses on material-based approaches to understanding institutions, post-conflict and post-colonial societies. She has recently completed a DFF-funded project Enduring Materialities of Colonialism: temporality, spatiality and memory on St Croix, USVI (EMoC) (2019-2024), and is the co-editor (with Máirtín O Catháin) of the Routledge Handbook of the Northern Irish Conflict and Peace (2024).

The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2023

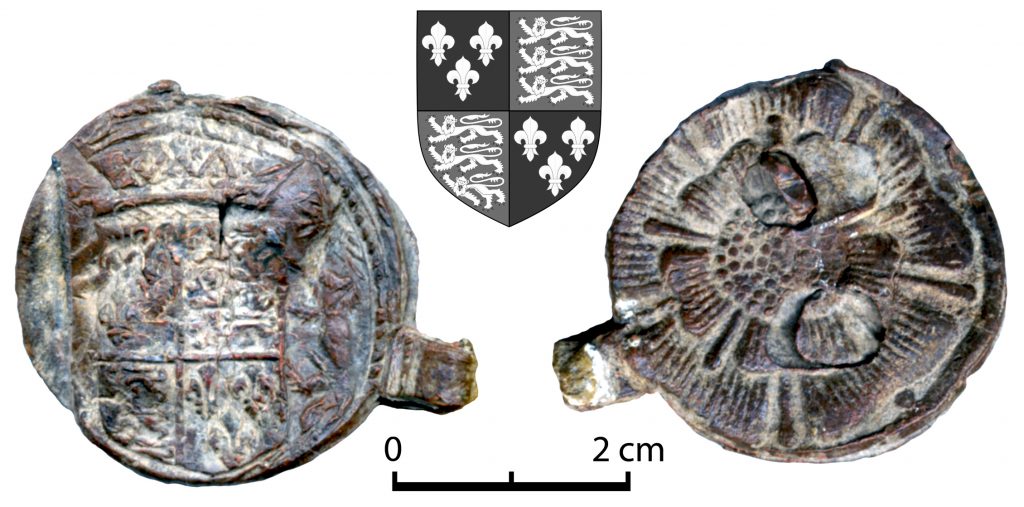

The Unexpected Side of English Cloth Seals: 16th- to 17th-Century Finds in Central and Eastern Europe: Professor Maxim Mordovin, Department of Hungarian Medieval and Early Modern Archaeology, Eötvös Loránd University

Cloth seals may be the “most Geoff Egan-topic”. He was the very first scholar who had started to deal with them on the scientific and interdisciplinary level, involving written sources and collecting all available data, including continental Europe. The last three decades show an enormous growth of the resources on cloth seals, both in print and online. These changes are equally valid for the Western European countries as well as for Central and Eastern Europe. The amount and the quality of the available information and the instruments of modern communication reveal some unexpected tendencies previously hidden by the deficit of data. One such interesting discovery is the situation with the English cloth seals all across the continent.

The role and the popularity of the English cloth in the late Middle Ages and Early Modern times is well known from the contemporary written sources. As the most popular among the high-quality fabrics, the English textiles by the end of the 16th century were widely traded to Poland, Hungary and the Ottoman Empire. The archival documents called it simply lundish, distinguishing several quality and colour groups of it. From Geoff Egan’s studies, we know that the better quality English cloth meant to be sold abroad was checked and sealed by the alnage office in London. The thousands of cloth seals from the UK and continental Europe prove this practice. The first interesting fact about all these ‘English-seals’ is that the known types in England and – in our case – in Central Europe do not coincide. The distribution of local types also shows some interesting tendencies. This paper presents the preliminary results of the evaluation of more than 500 English cloth seals found in the Carpathian Basin (Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, and Croatia) and Ukraine.

The lecture took place at Derby Museum of Making, on 6th December 2023

The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2022

Dr Rachael Kiddey: Archaeology as Sustainability

Tue, 6 December 2022

Drawing on a decade of collaborative contemporary archaeological fieldwork with marginalised people, this lecture explores what archaeology and cultural heritage studies can contribute to efforts to make the world a fairer and more sustainable place. Currently, we are surviving (to different degrees) in a climate which is increasingly politically and environmentally hostile. Research discussed in this lecture was driven not by the thought that we must ‘peg’ archaeology to something relevant for the sake of the discipline (or our jobs) but recognition that revolutionary potential of the past cannot be over-estimated, as the future depends upon how everything which has come before is assimilated and explained (Weil, 2001).

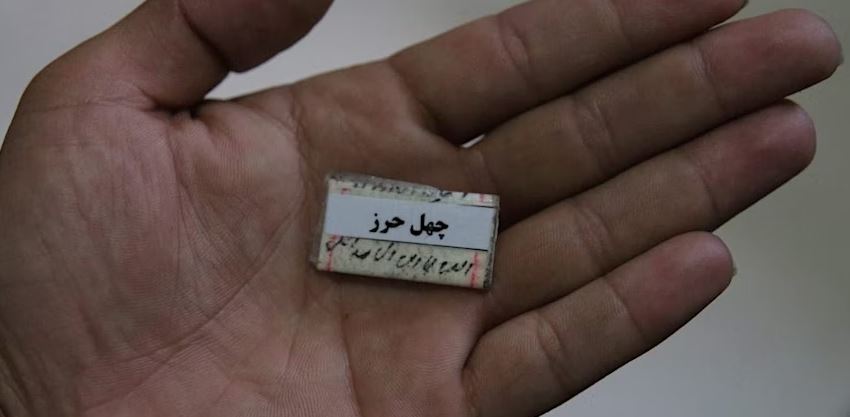

My doctoral research involved developing pioneering methods for conducting community archaeology with homeless people in Bristol and York, U.K. (Kiddey, 2017). Towards the end of that project, in 2014, I came to meet more and more people who were homeless in the U.K. but originally from places such as Afghanistan, Eritrea, Iraq, Somalia, and other countries ravaged by war and poverty. I came to think of homelessness as the domestic branch of a much broader story of human displacement, a centuries’ old and still unfolding story of dispossession and theft: a story undeniably a legacy of European colonialism and contemporary capitalism.

Between 2016 and 2022, I held two postdoctoral positions at the School of Archaeology, Oxford, during which I undertook a range of community heritage projects with diverse groups of forcibly displaced people in squats, on the street, and in day centres in Sweden, Greece, and the U.K. The people involved were of mixed age (12-58 years), mixed gender and sexual orientation, different educational, class, and religious backgrounds; they originally came from 8 different countries across Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and the Balkans and spoke 10 native languages; they had varied reasons for having fled their homelands. Yet within and across each group, individuals spoke beyond the social and cultural boundaries which separated them and found multiple commonalities in the experience of displacement. By inviting participation from anyone who wished to take part in a suite of complementary cultural heritage methods, I intentionally sought to create an activist community that would advocate for displaced people. We became a collective called Made in Migration (Kiddey 2021 & 2022).

Finding solidarity in similar lived experiences of displacement, the strength of the project lay in its ability to harness im/material encounters of life in forced displacement using a variety of established archaeological and cultural heritage documentary methods – photography, semi-structured interviews, and iterative deep mapping. As a collective, we applied data to produce two public heritage exhibitions, one virtual and one live, to challenge head on xenophobic narratives driven by reactionary populism. The explicit power of this community lay in our non-hierarchical methods of engagement and the confidence that this gave us to collectively tackle the racist homogenisation of displaced people by exposing the complex social and cultural backgrounds of those seeking refuge in contemporary Europe. In complicating populist narratives, we drove home the historical context and diversity of people and places – landscapes, borders, legal categories of citizenship, conflict – involved in global displacement, and we linked these with entwined ecological devastation, an increasing ‘push factor’ globally. Simultaneously, the project functioned as a therapeutic intervention for everyone involved, through reimagining themselves and others as mobile global citizens, ‘belonging’ in our right to peaceful and fulfilling lives. Made in Migration also tackled some of the problems inherent in undertaking political engagement in a hyper-mobile world by creating a virtual and, at times, sited-together archaeological community, from otherwise disempowered individuals, scattered by geopolitics and rendered unequal by accident of place of birth and associated privileges (or lack of). Made in Migration reasserted basic human needs and motivations, and our joint responsibility towards and reliance upon more-than-humans and planet Earth.

This event took place at Kelham Island Museum Alma Street Sheffield S3 8RY